Q. How did you get started and learn to make pottery?

A. Jenni: One day as a young girl, when my family was visiting friends, I saw my mom sitting at a pottery wheel on their porch. Mom had done pottery in high school, and now she was playing around with the wheel, without clay, trying to remember how the process went. I was seven years old at the time, and I asked her what the machine was and what she was doing with it. She told me it was a pottery wheel and explained to me briefly how it worked, saying, “With this, you can make plates out of mud.” I had loved to play in the mud since I was old enough to walk, so the thought of being able to make dishes out of mud was fascinating.

A. Jenni: One day as a young girl, when my family was visiting friends, I saw my mom sitting at a pottery wheel on their porch. Mom had done pottery in high school, and now she was playing around with the wheel, without clay, trying to remember how the process went. I was seven years old at the time, and I asked her what the machine was and what she was doing with it. She told me it was a pottery wheel and explained to me briefly how it worked, saying, “With this, you can make plates out of mud.” I had loved to play in the mud since I was old enough to walk, so the thought of being able to make dishes out of mud was fascinating.

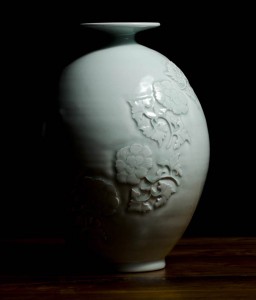

Hand sculpted pottery vase

Soon after that, children in our community were given the opportunity to take various craft workshops, and I signed up for pottery classes. I began with hand-building classes when I was seven, and when I turned twelve, I began to take lessons on the wheel. At the time I wasn’t very coordinated and working on the wheel was difficult for me. My teacher, Donna Arispe, was very patient, but in my second year of lessons, I still hadn’t fully caught on to working on the wheel. As it began to get close to our annual craft fair, Donna asked me if I would consider doing some hand-building, mainly so that I would have some completed projects for the fair. Then she added, hesitantly and gently, “Also, just think about it . . . and maybe pray and talk to your mom and see if pottery’s really your thing.” I had been doing so poorly with pottery that it did not seem like I had any aptitude or gift for it, and she didn’t want to see me waste time that I could spend learning something else. I went home and talked to my mom, but I just couldn’t give up pottery. “Mom,” I said, “I love it too much. I want to do this.” Mom said, “Well, . . . let’s pray and ask God to help you.” I can’t tell you exactly what happened—maybe it was just that when Donna asked me that question, it brought me to a decision to see how much I really did feel that pottery was what I wanted to do—but when I went back the next week, things started to “click,” and from that point on, my skills rapidly improved. In the fair that year, not only did I have some hand-built pieces, but I also had some finished pieces I’d thrown on the wheel.When I was sixteen, I entered a four-year apprenticeship in which I learned more about the other aspects of pottery, such as drying pots, loading and firing kilns, and mixing and applying glazes. Once I finished my apprenticeship, I began working full time for our fine-crafts business and helping to teach pottery workshops.

Q. What do you like most about pottery?

A. I enjoy throwing pieces on the wheel and teaching, especially children. I love to watch when a new student sits down at the wheel for the first time. Often, when children begin using the wheel, the first time they put their hands on a whirling piece of mud, the feeling takes them by surprise, and they start laughing. It’s so far outside their normal realm of experience that they can’t fathom how this mud is going to become a pot. I like to help other people learn to make pots. And having taught some of my students all the way from the basics of pottery to the point at which they could throw good quality pots on the wheel—that has been very rewarding. I also enjoy sitting and throwing pottery on the wheel myself. There’s a satisfaction and a fulfillment I get from taking raw clay and transforming it into something useful and beautiful.

Q. What advice would you give to someone who is just beginning and wants to learn pottery?

A. First I would say, “Take a class, and don’t try to learn it from a book.” Pottery is a craft that needs to be learned with hands-on instruction. Second, learn to be patient. It takes time to develop the skill needed to do pottery. Some people tend to be perfectionists, and sometimes they get bogged down right at the start and then give up because they can’t make perfect pots. I tell my students, “What’s perfect for you in your first year is not the same as what’s perfect for me in my twentieth year.” It’s good to strive for perfection, but don’t set your sights so high that you get discouraged before you’ve developed the skill you need to get there. Instead, take it a few days at a time. Start out with the basics and practice until you get them down, then move on. Don’t try to make ten-pound pots when you only know how to center three pounds of clay.

Q. What are your goals as a teacher?

A. I want to help students learn, in the shortest time possible, how to make beautiful pots; how to fire the kiln; how to do their glazes; and beyond that, how to develop an eye for form. Take a vase for example: if you have the shoulder (the widest part) of the vase halfway down, it will not appear balanced. The vase will be much more graceful and beautiful if you place its widest part a third of the way down. I’ve taken classes from master potters, and they will invariably tell you, “If you want to develop masterpieces, you have to develop an eye for form.” Although form is difficult for some people to acquire an eye for, it is something you can learn. I didn’t start out with it. It’s a skill I had to develop. But eventually it did “click” for me, and once I was able to see the shapes, I could help other people learn proper shaping, too.

Another of my goals is to help people see that making pottery is within their reach. Often people who visit our shop and watch us work say things like, “Oh, I could never do that. I don’t have the patience.” Of course, it is challenging to learn a new craft. It can even be a little frustrating at times. But when you love something enough, you’ll keep working at it until you overcome those difficulties, and you’ll develop the patience that you need in order to learn the craft. So, I want to inspire people that pottery isn’t just for some special class of people—anyone can learn to make a pot.

Q. Are there any recent projects you would like to tell us about?

A. For our annual fair in 2011, I made a large vase as a masterpiece project for a silent auction we held during the fair. Down the front of the vase, I carved a spray of peony flowers, and I glazed the vase in a Chinese celadon glaze. I drew my initial inspiration for this piece from several books I had read about ancient oriental potters and pottery. Celadon glazes are unique to the Orient, and they were made with local clays and minerals. I think they are beautiful and fascinating. To turn the correct color, celadons depend strongly on the firing of the kiln and the atmosphere inside the kiln, as do red glazes. The finish is very shiny and pearly-looking. Celadons are colored with a small amount of iron, in just the right combinations with other ingredients. Depending on the exact composition, they’ll turn a pearlescent blue or another very pale muted color, like olive green or sea-foam green. Traditionally, each color was specific to a particular region and reflected the composition of the local clay in that region. My vase, a wide jug with a very narrow top, was made from about eighteen pounds of clay. The opening in the top was only about an inch wide, and it’s difficult to get an opening that narrow on a piece as wide and tall as this one. To make it even more challenging, I made the lip lie almost flat—about four inches wide. I had to make several of these jugs to figure out how to do it. I was very pleased with the finished form, and I particularly enjoyed the carving. We were all pretty excited when it came out of the kiln the right color.

Q. What projects have you most enjoyed making?

A. In addition to the vase, I made another large piece that was quite challenging. At this point, it’s easy for me to make mugs and canister sets because I’ve practiced making them for so long. But for me to make a piece that’s challenging—that’s exciting. I find myself making the piece over and over again until I get it just right because it doesn’t always work the first time. (In fact, it quite often doesn’t work the first time.) This particular piece was made from about forty pounds of clay. The base is shaped like a very wide, shallow bowl, and the top comes back in to a relatively narrow opening. It had to be made in two pieces, and because of its size it took me awhile to figure out how to do that. In a class that I took on throwing, glazing and firing, the instructor asked me one day, “Is there any challenging piece you’d like to try, that you might need some help with?” He’s been doing pottery for 40 years and has a lot more experience than I do. So I described the piece to him—I actually had made a smaller one previously—and he said, “Well, that would be a challenging piece for me to make, too, but try it this way,” and he described how he would approach it. We tried his approach in class, and it worked. Once the class had ended, I came back home to our shop and tried making more pots like this. Five of my attempts failed, but one was successful. It’s still a very challenging piece for me to make, but I find great enjoyment making difficult pieces because it helps me grow by causing me to go beyond what is comfortable.

Q. What attribute do you feel best characterizes an excellent piece of pottery?

A. Two years ago I visited the Anderson Ranch Arts Center in Colorado. A thirteenth-generation potter from Japan lives as a guest resident there for a few months, twice a year. I didn’t have the opportunity to meet him, but I did see some of his work, and even something as simple as a small rice bowl was so perfectly balanced and so perfectly formed that you could tell, just by looking at the piece, that he had put a great deal of care into it. It was so perfectly done that—for lack of a better analogy— it was almost singing. Because it was made with so much care, it was perfectly in balance, and there was a harmony to it. So I would say, form and balance, along with the care that comes from striving for excellence.

Q. What, in particular, do you want your finished projects to express?

A We strive to let our finished products express the wholeness and the simplicity of our lifestyle. Over the past two years, I have visited a lot of other studios and looked at other potters’ work. From this, I’ve realized more fully how powerful clay can be as a medium for expressing what people’s lives are like—expressing what motivates them. A lot of the pottery I’ve seen saddens me because of what it expresses. Some potters I know of take pots and break them, then piece them back together. Or they’ll piece together a work to make it appear broken. They’ll explain to you that this sad thing happened, or that tragedy happened, and that is what this sculpture or this pot means. It becomes an expression of the brokenness of their lives. There are times when we, like everyone else, experience pain and sorrow, sadness and difficulty. But we’ve also found that in the context of a caring community of friends and loving people, we can find meaning in our pain and sorrows. Instead of expressing brokenness, we want our work to express the wholeness and simplicity of our lives, along with the strength and meaning that we find in that wholeness and simplicity.

Jenni Fritzlan has been making pottery for 24 years and teaching her craft for 13 years. She teaches at The Ploughshare and develops new pottery classes and curriculum. She also makes pottery and helps oversee the production of pottery for our fine crafts gallery, Heritage Fine Crafts.